Niger J Paed 2016; 43 (1): 46 - 50

ORIGINAL

Ahmed PA

Pattern of liver diseases among

Ulonnam CC

children attending the National

Mohammed-Nafiu R

Ballong J

Hospital Abuja, Nigeria

Nwankwo G

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v43i1.9

Accepted: 5th August 2015

Abstract :

Background: Diseases

socioeconomic classes while 23

of

the liver contribute to child-

(54.8%) had various forms malnu-

Ahmed PA (

)

hood morbidities and mortality.

trition. Common symptoms in-

Ulonnam CC, Mohammed-Nafiu R

Early recognition and proper man-

cluded jaundice (30; 71.4%), ab-

Ballong J, Nwankwo G

Department of Paediatrics,

agement of liver diseases can

dominal pain (17; 40.5%), fever

National Hospital Abuja

limit the progression to irrepara-

(15; 35.7%), abdominal swelling

Email: ahmedpatience@yahoo.com

ble damage which requires liver

(12; 28.6%) and bleeding (8;

transplant. However, there is scar-

19.0%). The signs included jaun-

city of data in the pattern of liver

dice (30; 71.4%), hepatomegaly

disease in Nigerian children.

(16; 38.1%) and splenomegaly (8;

Objective: To

describe the

pattern

19.0%). Twenty-four (57.1%) had

of

paediatric liver diseases among

chronic viral infections while the

children seen at the National Hos-

others included neonatal hepatitis

pital, Abuja.

syndrome and biliary atresia (6;

Methods: A

retrospective, de-

14.3%), acute hepatitis (6; 14.3%)

scriptive study conducted at the

and chronic hepatitis of unidenti-

Paediatric

Gastroenterology,

fied aetiology (4; 9.5%). Overall,

Hepatology

and

Nutrition

the mean values of the liver en-

(PGHAN) clinic and the Emer-

zymes and serum bilirubin were

gency Paediatric Unit (EPU) of

elevated while the mean values of

National Hospital Abuja, over a 5-

total serum proteins and albumin

year period (2009 – 2014). The

levels were reduced. Five (11.9%)

diagnosis of liver diseases was

children improved and were dis-

made from clinical and laboratory

charged, 15 (35.7%) were lost to

features. The data extracted from

follow up with three deaths.

the retrieved hospital records were

Conclusion: Risk

factors associ-

analyzed.

ated with liver diseases in this

Results: Forty-two

out of

52

study included age over 5 years

documented cases were analyzed.

and lower socio-economic classes.

The children were aged 2 months

Jaundice was the commonest clini-

to

15 years with the mean of 7.24

cal presentation while the most

±

4.77 years. Twenty-six (62.0%)

common aetiology was chronic

were aged >5 years (p>0.05).

Hepatitis B virus infection.

They comprised 31 (73.8%) males

and11

(26.2%)

females;

28

Key words: Children,

Liver

(66.7%) belonged to the lower

Diseases, Pattern

Introduction

viduals, with some age specific features and patterns

which differ from one region of the world to another.

1

Diseases of the liver may be infective, metabolic, toxic,

The clinical features of liver dysfunction may include

autoimmune, vascular or infiltrative in nature. With the

symptoms related to digestion problems such as abnor-

long list of the various aetiologies of paediatric liver

mal fat absorption and metabolism, coagulopathies,

diseases, about ten diseases constitute approximately

blood sugar abnormalities and immune disorders. Others

95% of all cases of cholestasis, and of these, biliary

include features of cholestasis, portal hypertension and

atresia and neonatal hepatitis are responsible for more

eosophageal varices.

than

60%. Diseases of the liver contribute significantly

1

to

childhood morbidity and mortality.

2,

3

The

clinical

Biliary atresia is a liver disease of the newborn which is

presentation of liver diseases vary greatly between indi-

characterized by abnormalities of the intra- and extra-

47

hepatic bile ducts, with incidence rates reported to vary

Methods

between 1 in 8, 000 and 1 in 21, 000 live births. Biliary

4

atresia is a major indication for liver transplantation

This was a retrospective, descriptive study of children

among children.

4

The autosomal recessive disorder,

managed over a five-year period (January 2009 to Janu-

Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, affects 1 in 1, 800 live

ary 2014) at the Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatol-

births and is the most common genetic cause of liver

ogy and Nutrition (PGHAN) clinic and the Emergency

disease in children. Viral hepatitis occurs in patients of

1

Paediatric Unit (EPU) of the National Hospital Abuja.

all ages, with about 500, 000, 000 people chronically

The PGHAN clinic runs every Wednesday as a special-

infected with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) or Hepatitis C

ist out-patient referral clinic while the EPU provides 24

virus (HCV) worldwide. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infec-

5

hours emergency services for all sick children. From the

tion causes both acute and chronic hepatitis which may

EPU, children with liver diseases are referred to the spe-

progress to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

cialist clinic for follow-up care.

The diagnosis of HBV rests on the demonstration of

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or anti-HBV core

The hospital records of the children with liver diseases

(anti-HB c ) IgM antibody.

Chronic HBV infection is as-

were retrieved from the Medical Information Depart-

sociated with the persistence of HBsAg and HBV DNA.

ment following due permission. The diagnosis of liver

The Hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes acute hepatitis,

diseases was based on the constellation of clinical and

which also progresses to chronic disease in more than

laboratory features. The data obtained included symp-

70% of affected individuals. Although end-stage liver

toms

and signs suggestive of liver diseases such as fe-

disease can occur in up to 10% of cases, fulminant hepa-

ver, jaundice, abdominal pain, swellings, itching, pale

titis has been described, though it is rare. The diagnosis

stools, bleeding, weakness, vomiting, anorexia, pallor,

of

HCV is suggested by the presence of anti-HCV anti-

hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and ascites. The results of

bodies and confirmed by polymerase chain reaction for

liver function tests such as serum levels of alanine ami-

HCV RNA. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection occurs

notransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST),

only in patients who have HBV infection. HDV is pri-

Alkaline phosphatase (AP), prothrombin time (PT) and

marily associated with intravenous drug abuse and it

partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international nor-

usually aggravates on-going liver disease in children

malization ration (INR), serum protein and albumin

with HBV infection. In addition, Hepatitis E virus

were also recorded. The results of viral serology markers

(HEV) occurs in epidemics in parts of the world that

such as HBsAg, HbeAg, and HBV-DNA for hepatitis B

have poor sanitary conditions. Disorders of fat metabo-

infection; HCV, anti-HCV and HCV- RNA for hepatitis

lism usually present in late infancy and early childhood

C

infection as well as HIV screening were also captured.

while neoplastic diseases of the liver among children

Other investigation reports reviewed were liver biopsies,

and adolescents differ from the types observed among

abdominal ultrasonograpy and abdominal computed

adults.

tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

reports. Four patients had liver biopsies done, while ge-

Chronic hepatitis is traditionally defined as an inflam-

netic information and enzymatic assay could not be done

matory condition of the liver characterized by the persis-

due lack of facilities.

tence of biochemical and histologic abnormalities for

more than six months. However, irreversible changes

The children were classified into three broad categories;

may occur in children within those six months. These

namely, infective, non- infective (metabolic, congenital,

chronic hepatitis conditions may be viral infections,

cholestatic, neoplastic) and idiopathic liver diseases.

autoimmune processes, and exposure to hepatotoxic

Specific diagnoses were categorized as chronic liver

drugs as well as cardiac, metabolic, or systemic disor-

disease (CLD) when symptoms persisted beyond six

ders. Most cases of acute hepatitis in children resolve

months of follow-up care, with or without identifiable

within three months. Progressive liver dysfunction af-

viral serological markers. The group classified as idio-

fects childhood nutrition and may be complicated by

pathic had no identifiable cause while acute hepatitis

growth retardation. Unfortunately, the timely recogni-

had symptoms with resolution within less than six

tion of severe liver disease in children remains a major

months and were negative for serological markers. A

challenge. One factor contributing to this challenge is

few patients were screened for cytomegalo-virus (CMV)

the manifestation of injuries to the paediatric liver in a

and toxoplasmosis. Facilities for other serological mark-

finite number of ways, hence different hepatic disorders

ers were not available. Demographic characteristics and

often have virtually identical initial presentations. Early

outcome of the care for the children were obtained and

intervention may reduce the progression of liver diseases

classified. Data were analyzed using SPSS 20 version.

from initial inflammation to scarring with irreparable

Pearson Chi-squared test was used for the comparison of

damage in the form of cirrhosis and/or cancerous trans-

categorical data and p values <0.05 were considered

formation.

1,

4, 6

Therefore, the aim of this review was to

statistically significant.

determine the pattern of liver diseases among children at

the National Hospital, Abuja.

Results

A

total of 52 cases were documented in the records from

the clinic and the EPU, out of which 42 cases were ana-

48

lyzed. The age of the children ranged from 2 months to

Table 4: Diagnoses

among children

with liver

diseases

15years with the mean (± SD) of 7.24 (± 4.77) years.

Diagnoses

Number (%)

There were 31 (73.8%) males and 11(26.2%) females

CLD

(viral hepatitis)

24

(57.1)

with a male-to-female ratio of 2.8:1. Sixteen (38.0%)

Acute

hepatitis

6

(14.3)

subjects were aged 5 years and below; half of these were

CLD

(unknown cause)

4

(9.5)

aged

less than one year. The remaining 26 (62.0%) sub-

Neonatal hepatitis syndrome (NHS)

3

(7.1)

jects were older than five years. The differences in the

Biliary atresia

3

(7.1)

proportion of children in the comparison age groups

Fulminant hepatitis

2

(4.8)

were not significant (p = 0.897) (Table 1). The distribu-

Cholestatic hepatitis(ciliopathy/ choledochal cyst)

2

(4.8)

Portal hypertension with oesophageal varices

2

(4.8)

tion according to the socioeconomic classes were as

Malignancy (hepatoblastoma)

1

(2.4)

follows; 28 (66.7%) in the lower socioeconomic class, 6

Galactosaemia

1

(2.4)

(14.3%) and 8(19.0%) in the upper and middle socioeco-

Some children had more than one diagnostic classification; CLD –

nomic

classes respectively. Nineteen (45.2%) of the

chronic liver disease

subjects were fully vaccinated for HBV during infancy;

19

(45.5%) had normal nutritional status while 23

CLD of viral aetiology formed 57.1% of all the children

(54.8% had various forms malnutrition with no statisti-

studied. Non- infective cases, namely, biliary atresia,

cally significant difference in the proportions (p =

cholestatic hepatitis, hepatoblastoma and galactosaemia

0.058) (Table 2).

accounted for 21.4% s while idiopathic cases included

acute hepatitis 14.3%, CLD 9.5% and NHS 7.1% as

Table 1: Age

and sex

distribution of

children with

liver

shown in Table 4. Of the 24 (57.1%) subjects positive

diseases

with viral serological antigen markers, 18 (75.0%) were

Age

groups

Males

Females

Total (%)

positive for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg); 10

(years)

with HbeAg and 6 with elevated HBV DNA viral load.

0-5

12

4

16(38.0)

Χ2

= 0.217

Five (11.9%) children were positive for hepatitis C anti-

>5-10

10

3

13(31.0)

gen and anti- HCV antibodies, some with co-infections

>10- 15

9

4

13(31.0)

p =

0.897

(Table 5).

Total

31

11

42(100.0)

Table 5: Distribution

of Infective

children with

liver diseases

Table 2: Distribution

of children

with liver

diseases according

to

age and nutritional status

Infective category

Number (%)

Age

groups

Normal

Under-

Over-

Total

HBV( 10 HbeAg pos; 8HbsAg carriers)

18

(42.9)

(years)

nutrition

weight

HBV-HCV co-infection

1

(2.4)

Χ

=9.125

2

0-5

4

9

2

16

HCV

(HCV antibodies)

2

(4.8)

>5-10

7

2

5

13

p

=

HCV-HIV co-infection

1

(2.4)

>10- 15

8

3

2

13

0.058

HCV-CMV co-infection

1

(2.4)

Total

19

14(33.3)

9(21.4)

42

CMV-Toxoplasmosis co-infection

1

(2.4)

(45.2)

(100.0)

The mean (±SD) values of liver enzymes and serum

Figures in parentheses represent percentages of the total in the row

bilirubin were elevated, with low total serum proteins

and albumin levels (Table 6). Twelve (28.6%) subjects

The most common symptoms included jaundice (30;

received treatment with antiviral agents and interferon; 5

71.4%), abdominal pain (17; 40.5%), fever (15; 35.7%),

(41.7%) of these 12 children improved with sero-

abdominal swelling (12; 28.6%) and bleeding

conversion and were discharged. One subject with bil-

(8; 19.0%). Physical findings included hepatomegaly

iary atresia had liver transplant overseas, while 15

(16; 38.1%), pallor (14; 33.3%) and splenomegaly

(35.7%) were lost to follow up (Figure1). There were

(8; 19.0%) as shown in Table 3.

three deaths, two of which had unknown aetiology and

presented with encephalopathy

Table 3: Frequencies

of symptoms

and signs

of liver

diseases among

children

Table 6: Liver

Functions profile

of children

with liver

diseases

Features

Frequencies

Percentages

Parameters

Mean

Std. Deviation

Symptoms

values

Jaundice

30

71.4

Serum Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)IU/L 135.23

171.81

Abdominal pain

17

40.5

Serum Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)IU/L

176.80

376.40

Fever

15

35.7

Serum Alkaline phosphatase (AP)IU/L

261.23

196.22

Abdominal swelling

12

28.6

Serum Gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT)

Vomiting

8

19.0

IU/L

155.73

259.66

Weakness

8

19.0

Conjugated serum bilirubin (umol/L)

22.15

65.37

Bleeding

8

19.0

Total serum bilirubin (umol/L)

79.05

126.21

Pale stool

7

16.7

Total serum proteins (g/L)

33.86

35.28

Anorexia

7

16.7

Serum albumin (g/L)

16.70

17.85

Itching

4

9.5

Unconsciousness/restless

2

4.8

Signs

Hepatomegaly

16

38.1

Pallor

14

33.3

Splenomegaly

8

19.0

Ascites

5

11.9

Coma

2

4.8

49

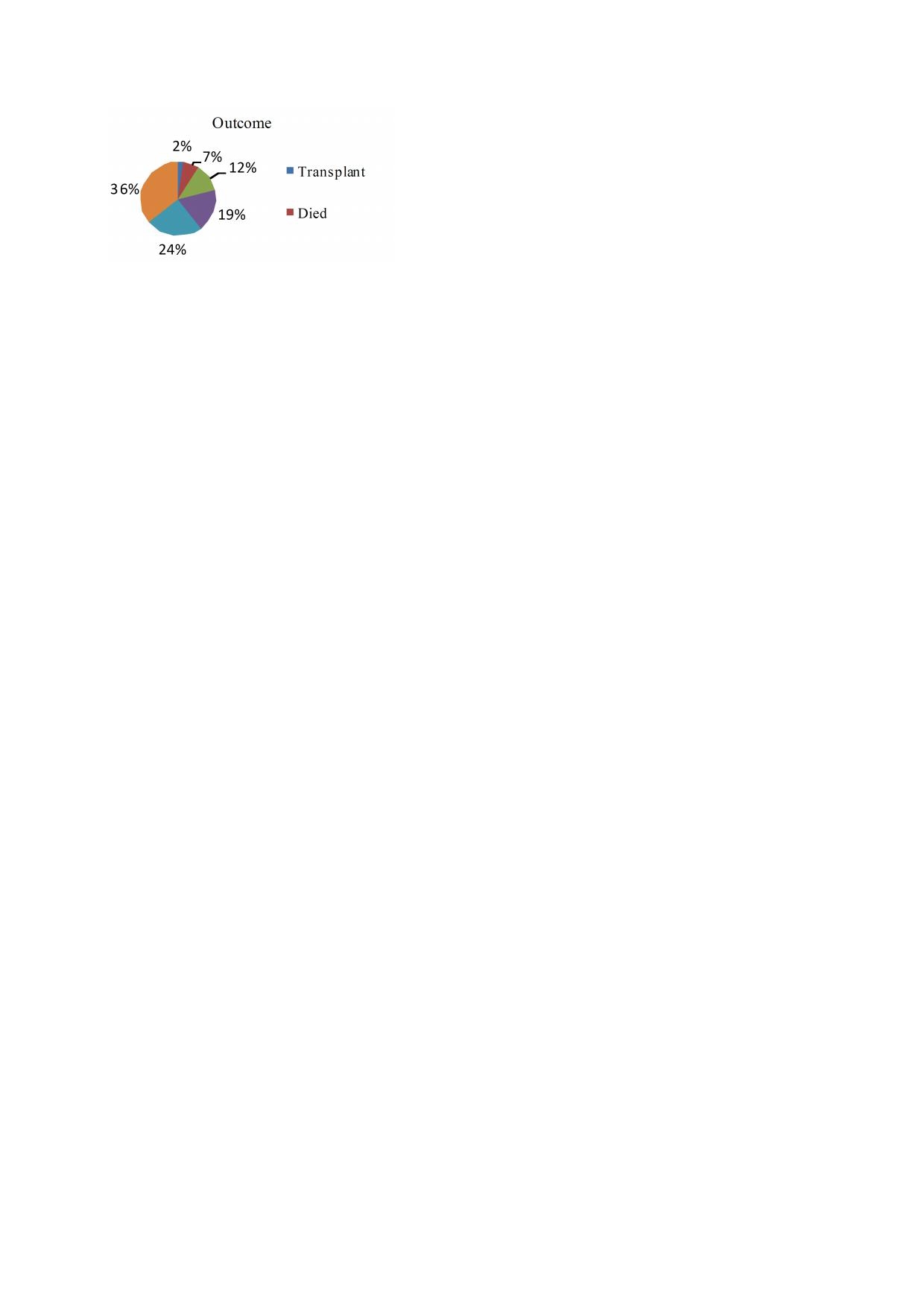

Fig 1: Outcome

of children

with liver

diseases

and bleeding. In a report by Dar

et al

10

on

186 children

Outcome

less

than 18 years, jaundice was reported among all the

2%

children presenting with acute hepatitis, and 75 percent

7%

of

those presenting with chronic liver diseases. Some

12%

Transplant

children in this report, presented with features of portal

36%

hypertension and esophageal varices such as hepa-

19%

Died

tosplenomegaly, ascites, gastro-intestinal bleeding and

encephalopathy. These features were suggestive of fairly

24%

advanced liver diseases with decompensation present at

presentation. Such children were classified under grades

B

and C of the Child- Pugh scores. The children had

deranged values of laboratory parameters; specifically

Discussion

elevated liver enzymes levels and bilirubin levels and

low

albumin levels. These findings suggested both acute

This

hospital-based descriptive review focused on the

and

chronic liver pathology. According to the Child-

Pugh

scoring system, total serum bilirubin greater than

10

spectrum

and

magnitude

of

liver

disorders

among children aged less than 16 years who were man-

50µmol/l, serum albumin less than 2.8g/dl, prolonged

aged over a five-year period in a tertiary health centre.

prothrombin time and INR level greater than 2.3, moder-

The demographic characteristics suggested that males

ately severe ascites and hepatic encephalopathy pre-

and

children from lower socioeconomic classes were

dicted mortality. Some of the children in this report had

more

frequently affected by liver diseases.

3,

7- 9

The

age

chronic liver disease that met the above-stated criteria,

of

the children in this study ranged between 2 months

though endoscopy was not available for the children

and

15 years with the mean of 7.24 ± 4.77 years. This

with

bleeding varices.

was

similar to the findings reported by Dar

et al ,

10

who

reported the mean age of 9.34 ± 4.8 years (range of 1-18

The most common aetiologic group in the present study

years). The age data in the present study were higher

was

infective (viral) hepatitis, especially Hepatitis B

than

the mean age of 4.8 ± 0.3 years (range 5 months

infections. This report was similar to the findings in a

and

14 years) reported by Alam et al . Children aged

9

retrospective analysis of 300 children with various liver

over five years accounted for 62 percent of the study

diseases, at two major teaching hospitals of Karachi

population in the present report. This observation may

where acute viral hepatitis and its sequelae were the

most frequent (31 percent) of all hepatic ailments. The

8

suggest exposure to preventable liver infections early in

life in this population. Various forms of malnutrition

5

World Health Organization (WHO) reported that about

(underweight, marasmus and overweight) were observed

two billion people are infected with the Hepatitis B virus

among 54.8 percent of the children studied while 21.4

(HBV). In highly endemic areas, HBV infections in chil-

percent was overweight. Under- nutrition may be a di-

dren are most commonly spread from mother to child at

rect consequence of liver diseases while overweight and

birth or from person to person in early childhood and

adolescence. Children aged above five years accounted

5

obesity are predisposing conditions. In a retrospective

study of 79 children with chronic liver diseases whose

for

66.7 percent of all the known infective cases in this

mean

age was five years, reported by Al-Lawati

et al ,

11

study. Reports have shown that the persistence of viral

growth retardation was recorded among 75 percent of’

infections

in the liver predisposes to cirrhosis and hepa-

the

children.

tocellular carcinoma. The diagnosis of HBV was based

on

sero-positivity for HbsAg and HbeAg as well as the

The recent rise in the prevalence rates of obesity and

HBV DNA viral load in a few cases who could afford

overweight in the United States has resulted in the emer-

the test where it is available. Children with detectable

gence of non- alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as

HBsAg for a period up to six months with or without

the leading cause of chronic liver disease among chil-

concurrent HBeAg were considered to have chronic

dren and adolescents in the United States.

12

In

addition,

HBV infection. The presence of HBeAg only indicates

emerging data suggest that children with non-alcoholic

that the child is highly infectious. Other makers of infec-

steatohepatitis (NASH) progress to cirrhosis which may

tion such as the assay of immunoglobulins to hepatitis

ultimately increase liver-related mortality.

12

However,

core antigen (IgMHBcAg) and the newer HBsAg quan-

due to non-availability of advanced biochemical labora-

tification assay are not yet routinely evaluated due to

tory and limited facilities for biopsies, the inability to

non-availability and high cost. Hepatitis C infection

search for some of these metabolic disorders in the pre-

cases were also recorded in this study, though less com-

mon than expected.

13

sent report may be a limitation in this study. Liver his-

Most often, HCV infection is ac-

tology remains the gold standard for assessing hepatic

quired at birth in the younger child but adolescents can

steatosis. Nevertheless, only four (9.5 percent) children

also acquire the infection through activities which facili-

in

our series had liver biopsy. This rate was lower than

tate blood contacts such as intra venous drug use, shar-

ing

needles and high-risk sexual behaviors.

14

the 30/164 (18.3 percent) reported in the Dhaka Shishu

The

odds

Hospital study.

9

of

a child acquiring HCV from an infected mother is

Jaundice was the most common clinical feature in over

1:20.

14

Reports show that spontaneous clearance of

70

percent of the children in this study. Others included

HCV infection can occur in about 40 percent of new-

abdominal pain and swelling, fever, vomiting, weakness

borns who acquired the disease vertically, by the age of

50

two

years, and sometimes up to 7 years. Co-infections

14

tem human disorders caused by a multitude of largely

were recorded in the present study, with HBV/HCV co-

unrelated genes that affect ciliary structure/function. The

infection and HBV/HIV co-infection. HBV/HCV co-

mode of inheritance is recessive, either autosomal or X-

infected persons have been shown to have more severe

linked, with strong evidence of genetic modifiers which

determine expressivity.

16

liver injuries and higher chances of progression to cir-

rhosis or cancerous transformation. CMV co-infections

15

with HCV and toxoplasmosis were also identified in this

Some children had liver diseases of unknown aetiology,

report. This observation underlines the importance of

most of whom had complete resolution and were dis-

charged home. Dar et

al reported 52 percent with no

10

testing for other non-hepatitis virus in any suspected

case of liver disease.

aetiology (cryptogenic) in a hospital- based descriptive

study. Some of the reasons limiting diagnosis of specific

Neonatal hepatitis syndrome and biliary atresia ac-

liver patterns included the non-availability of routine

counted for 14.2 percent of liver diseases among infants

biopsies, specific diagnostic tools for HbsAg quantifica-

in

this study. Biliary atresia presenting as cholestatic

tion levels, routine HBV- DNA (viral load) and mag-

liver disease, may be caused by intra-or/and extra-

netic resonance elastography (MRE) which accurately

hepatic bile ducts obstruction. It is the major indication

detects fibrosis. About a third of the children in the pre-

for liver transplantation in children. Early presentation

4

sent

study were lost to follow up for various reasons

is

most desirable and portoenterostomy surgery (Kasai

such

as poor finances and non-availability of immediate

procedure) is best carried out within 100 days of life.

cure.

The

success of this procedure in the establishment of

bile

drainage, is variable and up to 40 percent of chil-

dren

may develop significant fibrosis and progress to

Limitation

require liver transplantation within the first few years of

life. One of the children in the present study had liver

4

Incompleteness and loss of data were noted in the pre-

transplant within the first two years of life. Other rare

sent

study. Other limitations included lack of adequate

causes of liver disease, such as ciliopathy, hepatoblas-

investigative capacity mostly due to non-availability of

toma

and galactosaemia were seen in this report. A case

advanced biochemical laboratory and financial con-

of

liver ciliopathy presented acutely with massive GI

straints.

bleeding, hepatomegaly and ascites with deranged liver

functions. The diagnosis was made with liver biopsy.

Conflict of interest: None

Ciliopathies are an emerging class of genetic multisys-

Funding: None

References

1.

D’Agata ID, Balistreri WF.

7.

Burki MK, Orakzai SA. The

13.

Mack CM, Gonzalez-Peralta RP,

Evaluation of liver disease in the

prevalence and pattern of liver

Gupta N, Leung D, Narkewicz

paediatric patient. Paediatrics in

disease in infants and children in

MR,

Roberts EA, Rosenthal P,

Review 1999; 20 (11): 376 -390.

Hazara Division .

J Ayub

Med

Schwarz KB. NASPGHAN prac-

2.

Okonkwo U, Nwosu M, Boju-

Coll Abbottabad 2001; 13(1): 26-

tice guidelines: diagnosis and

woye B. The predictive values of

28.

management of hepatitis C infec-

the

Meld and Child-Pugh scores

8.

Mehnaz A, Billo GA, Zuberi SJ.

tion in infants, children and ado-

in

determining mortality from

Liver disorders in children. J Pak

lescents. J

Pediatr Gastroenterol

chronic liver disease patients in

Med Assoc 1990; 40: 62- 64.

Nutr 2012; 54:838-55.

Anambra state, Nigeria. Internet

9.

Alam MJ, Ahmed F, Mobarak

14.

Narkewitz MR. Hepatitis C in

J Gastroenterology 2010; 10 (2).

R,

Arefin S, Tayab A, Tahera A,

children. American liver founda-

3.

Sabir OM, Ali AB, Algemaabi O.

Mahmud S. Pattern of liver dis-

tion online article. Link:http://

Pattern of liver diseases in Suda-

eases in children admitted in

www.liverfoundation.org/

nese children. Sudan

J. Med

Sci

Dhaka Shishu Hospital. Int

J

chapters/rockymountain/

2010; 5(4): 285-288.

Hepatol 2010; 1(3):18-24

doctorsnotes/paediatrichcv/. Ac-

4.

Petersen C. Pathogenesis and

10.

Dar

GA, Zarger SA, Jan K,

cessed on 11/11/2014.

treatment opportunities for bil-

Malik MI, Mir TA, Dar MA.

15.

Chu

CJ, Lee SD. Hepatitis B

iary atresia. Clin

Liver Dis.

2006;

Spectrum of Liver Diseases

Virus/Hepatitis C Virus Co-

10:73 – 88.

among Children in Kashmir Val-

infection: Epidemiology, Clinical

5.

World Health Organization.

ley. Academic

Med J.

India 2014;

Features, Viral Interactions and

Prevention & Control of Viral

2(3):80 – 6.

Treatment. J

Gastroenterol Hepa-

Hepatitis Infection: Framework

tol. 2008; 23(4):512-520 .

for

Global Action. WHO 2012;

Eun

Lee J, Gleeson JG Review:

.

11.

Al-Lawati TT;George M;Al-

16.

hepatitis@who.int.WHO.int/

Lawati FA. Pattern of liver dis-

A

systems-biology approach to

topics/hepatitis

eases in Oman. Ann

Trop Paedi-

understanding the ciliopathy dis-

6.

Akinbami FO, Venugopalan P,

atr 2009; 29(3):183-9.

orders. Genome

Medicine 2011,

Nirmala V, Suresh J, Abiodun P.

12.

Loomba R, Sirlin CB, Schwim-

3:59.

Pattern of chronic liver disease in

mer

JB, Lavine JE. Advances in

Omani children- A clinicopa-

Paediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty

thological review. West

Afr J

Liver Disease. Hepatol

2009; 50

Med 2004; 23(2):162-166 .

(4):1282-1293.